In our previous article on the EU's Fuel Quality Directive (FQD) we discussed the obligations on transport fuel and energy suppliers under the 2009 amendments to the FQD. The FQD target of a 6% reduction in the greenhouse gas (GHG) intensity of transport fuel and energy by 2020 (2010 baseline) was transposed into Irish law in April 2017.

In this article we examine the progress that Ireland’s suppliers have made towards the target and some of the challenges facing them.

Two targets

There are strong links between the 10% RES-T target set out in the Renewable Energy Directive (RED) and the FQD 6% GHG reduction target. We explored these links in our previous article. Compliance with both will rely to a large extent on substituting fossil fuel with biofuel.

However, meeting one target will not ensure compliance with the other. There are several reasons for this, including the fuel mix, the carbon intensity of the biofuel placed on the market and, most importantly, the fact that the RED allows for double counting of biofuels produced from 'wastes, residues, non-food cellulosic material, and ligno-cellulosic material'. Such biofuels are awarded two biofuel certificates per litre through the biofuels obligation scheme (BOS) and they make up the majority of the biofuels placed on the Irish market. In 2015, 76% of biofuel (by energy) placed on the Irish market was double counted. All of this was biodiesel, accounting for 99% of all biodiesel on the market in 2015. 74% of the double-counted biodiesel was sourced from used cooking oil (UCO), 21% from category 1 tallow and 4% from spent bleaching earth.

Biofuel cannot be double counted under the FQD; this is the primary reason why the two targets are not aligned.

Ireland’s progress towards FQD compliance

We have used the methodology set out in Council Directive (EU) 2015/652 and data from the Biofuel Obligation Scheme Annual Report 2015 to calculate the progress of Ireland’s suppliers towards the 6% FQD target. The overall GHG intensity of the road transport fuel sold in Ireland in 2015 was 91.9 gCO2eq/MJ, which was just 2.3% lower than the 2010 fuel baseline standard (94.4 gCO2eq/MJ).

This is equivalent to a shortfall of approximately 550,700 tCO2eq, relative to the 6% target.

How to reach the 2020 targets?

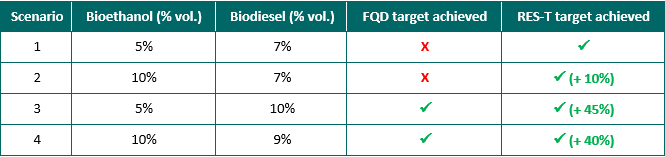

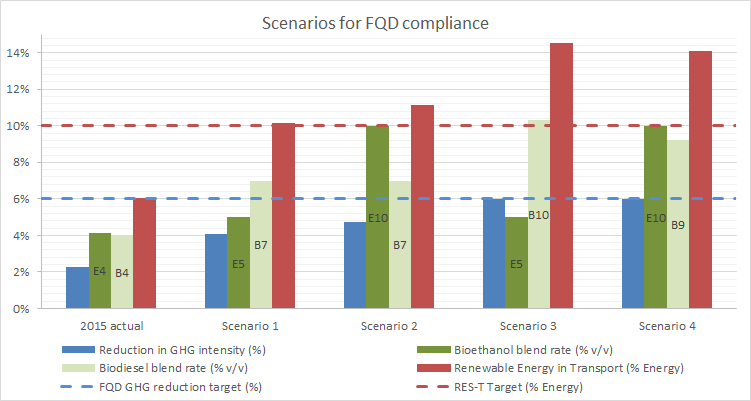

To illustrate the scale of the challenge Ireland will face in overcoming this shortfall, while also meeting the RES-T target, we set out four different scenarios, each of which is based on a different biofuel blend rate in gasoline and diesel for 2020. In all of the scenarios the ratio of diesel to gasoline is 69:31 (by volume) and 99% of biodiesel is double-counted, reflecting supply patterns in 2015.

The figure below illustrates how each of the four scenarios compare to the FQD and RES-T targets; data for the 2015 period is also provided for comparison.

Scenarios 1 & 2 illustrate the limited potential of bioethanol to contribute to the FQD target, even in circumstances where the RES-T target could be achieved. Even though the bioethanol blend rate in scenario 2 (10%) is twice that in scenario 1 (5%), the difference in the attributable GHG reduction (blue bar) is marginal. This is because the carbon intensity of bioethanol is, on average, much higher than that of biodiesel and because, as a proportion of the road transport market, gasoline accounts for only 31%, by volume.

Electric vehicles

Contributions from upstream emission reductions (UERs, see previous article) and electric vehicles (EVs) have been omitted from our analysis. Suppliers’ UERs would contribute towards the FQD target but not towards the RES-T target, while the use of EVs would contribute to both the FQD and RES-T targets. However, UERs are not yet available and there is little certainty about how a UER system will operate. Electricity in EVs will contribute, but given the low penetration of EVs in the market at present and the relatively modest projections for growth to 2020, it is not expected to make a significant contribution.

Missing the FQD by 1.9% (as depicted in scenario 1) would require 282 kt of CO2eq to be offset by UERs or EVs. If EVs alone were to compensate for the shortfall, an additional ~300,000 EVs would be needed in the road transport fleet.

Blend wall limitations

Scenarios 3 & 4 illustrate how the FQD target could be achieved using biofuels alone, i.e. with no reliance on EVs or UERs. Both scenarios show a requirement for significantly more biofuel (around 9% blend) than needed for RES-T compliance alone. However, this could not be achieved using conventional biofuels because of ‘blend wall’ limitations (10% ethanol in gasoline and 7% FAME in diesel).

Biodiesel will almost certainly play a more significant role than bioethanol in assisting suppliers achieve compliance because:

- The market share of diesel is larger than that of gasoline.

- The GHG intensity of biodiesel is less than half that of bioethanol (based on 2015 averages).

- There are significant logistical, technical and commercial obstacles to be overcome, before 2020, in order to introduce E10 (gasoline with 10% bioethanol) to the Irish market.

Furthermore, it is likely that biodiesels that are not restricted by the blend wall, such as hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO), will play a particularly important role if the FQD target is to be met.

Other options

Biofuels used in non-road transport can also contribute to the FQD and RED targets. A 2015 amendment to the FQD permits Member States to allow biofuel in aviation to contribute towards the FQD target. In the UK, for example, a recent consultation by the Department for Transport has identified biofuel in aviation as a potential contributor to achieving targets and the sector will benefit from policy support.

Other renewable fuels, such as hydrogen and biomethane, can also make a contribution to both the FQD and RED targets.

Conclusion

Complying with the FQD target will be very challenging. There is uncertainty surrounding the contribution from EVs and UERs and, therefore, it is likely that biofuels will be the primary means of reducing the GHG intensity of transport fuel. There are, however, significant barriers to increasing the volume of biofuel on the market and with only three years to go until the compliance deadline, the means by which Ireland's fuel and energy suppliers will reach this target are far from certain.

This insight was updated in July 2017 to include reference to the transposition of article 7a of the Directive into Irish law via SI 160 of 2017.